By DAVID BROOKS

Staff Writer

![]() MANCHESTER – Even as FairPoint Communications settled a long strike involving many of its line workers, the company made another move that says at least as much about the state of the telephone industry, preparing to turn part of their Manchester facility into a data center and push into a competitive business that has nothing to do with Ma Bell.

MANCHESTER – Even as FairPoint Communications settled a long strike involving many of its line workers, the company made another move that says at least as much about the state of the telephone industry, preparing to turn part of their Manchester facility into a data center and push into a competitive business that has nothing to do with Ma Bell.

“That has really become the driver: We’re converting from the phone company to a technology company,” said Chris Alberding, the company’s vice president of product development.

Data centers contain huge racks of computers operated for other firms or institutions such as hospitals, universities and governments, either as backup in case of disaster or as an outsourced facility.

A number of companies operate data centers in the region. For example, not too far from the FairPoint central office at 770 Elm St., FirstLight Fiber has a much larger data center obtained when it bought G4 Communications last fall.

“The industry is growing,” said Maura Mahoney, a senior director of marketing and product management at Albany, N.Y.-based FirstLight, who is based in the firm’s Nashua office on Ledge Street. “What we’re seeing is there are a number of industries looking to offload their servers and their applications.”

Expensive business

ColoSpace of Rockland, Mass., an industry pioneer that has operated data centers for two decades, has a large facility in Bedford. Wayne Sawchuk, cofounder of ColoSpace, welcomed FairPoint’s competition but wondered if a company built to operate the partially regulated telecommunications business can make it in data centers.

“The question is will they spend the money that data centers have to spend today to be really redundant?” said Sawchuk. He gave one example: “They can’t rely on just one generator. In Bedford we have three generators. … I’ve never seen a (central office) that had three generators.”

“I spend a couple million dollars a year just upgrading everything – new network, rewiring, replace battery,” he said.

Sawchuk also noted that FairPoint’s reputation is not always the best, due to well-publicized stumbles after it bought Verizon’s landline business in 2008 and went into bankruptcy. This, he said, could make customers leery because data centers are so vital.

“We have one customer, a medical customer, that handles 90,000 appointments a day. If their computer network goes down, it’s a disaster,” he said.

Central offices

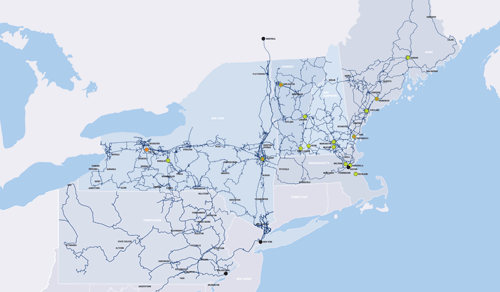

FairPoint has one big advantage over competitors because it owns lots of buildings suitable for data centers. They are its central offices, often called COs, built over the year to hold the switches and machinery that have long connected the phone network, most with tight security, power backups, separate entrances and fiber-optic connections for moving data.

“We have over 300 COs: big, high-security concrete buildings that have been housing phone service for last 100 years. As technology has improved and has gotten small, it has opened up more and more space in these facilities,” said Alberding.

The company tested the concept last summer in the Lakes Region.

“We’ve got this Laconia central office, with an entire floor that’s empty. We said, why don’t we parse off a portion of that, market it to customers. … Before before end of the year was up, we had exceeded our forecast,” said Alberding.

That success led them to separate 4,000 square feet in the Manchester central office and launch a new data center. It will be focused on services, include “remote hands” services such as swapping out servers, with future plans to provide on-site engineers for more complex work.

FairPoint needs new business because what is known in the industry as POTS – plain old telephone service – is slowly fading. The number of access lines in New Hampshire, Vermont and Maine, which make up 80 percent of FairPoint’s business nationwide, has been falling by around 7 percent a year as people switch to cell phones, voice over Internet, or phone service bundled with their cable TV connection.

As a result, FairPoint has been counting more heavily on other parts of its business. These include Internet service via DSL over copper lines or in some areas fiber-optic lines, carrying signals from cell towers into the main phone network, and various industry applications. Data centers fit in the latter category.

Geography matters

Data centers would seem to be independent of geography, since information can move at the speed of electrons to anywhere, but location is actually important.

“Customers want to have applications off site, but close enough that if there’s an issue they can drive to the site and reboot servers themselves,” said Mahoney of FirstLight, which has data centers in Albany, N.Y., where it started, as well as Lebanon and Keene, and one in Vermont.

Alberding put it this way: “The IT guys want to be able to put their hands on the equipment, just in case.”

FairPoint is unlikely to establish a data center in Nashua any time soon, since Manchester covers the area.

“We’d never rule out any facility, but the next step is likely to be Maine and Vermont,” said Alberding.

The incentives for businesses to pay for data center space, often called co-location, vary. Many hospitals cite HIPAA, the federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, which sets strict standards about handling of patient and medical data. Having copies of your data far enough away that they will survive a disaster such as widespread flooding is also necessary in many financial industries to meet auditing requirements.

In Laconia, Alberding said, “Four of the first five customers were in Maine. They had to be greater than 60 miles away to meet their disaster requirement needs.”

David Brooks can be reached at 594-6531, dbrooks@nashua telegraph.com or @GraniteGeek.